Wildfires are an unfortunate part of reality around the world. For those who live in suburban or in wooded areas, the risk of losing everything to a wildfire is very real. On January 7th, 2025 that risk became reality for thousands of Southern California residents. Several fires erupted in the foothills of Los Angeles, Malibu, Pacific Palisades and Altadena and burned for 24 days (until January 31st, 2025) and claimed 29 lives. The estimated costs are expected to be between $28 billion and $53 billion. The severe damage in Los Angeles in 2025 made world news and environmentalists raised an interesting questions, are wildfires getting worse?

Damage Caused by Wildfires

California wasn’t the only region of the world affected by wildfires. 2025 was Canada’s second worst fire season with more than 16 million acres burned by mid-August. Most of the fire damage occurred in the Manitoba and Saskatchewan regions. 2023 was the worst year on record for Canada with more than 30 million acres of wilderness destroyed by fires.

The physical fire may be contained to a region, however their effects are felt around the world. Smoke from the 2025 Canadian wildfires reached central Europe in just a few days. It’s estimated there were 4,100 acute-smoke related deaths in the U.S and 22,000 premature deaths in Europe as a result of the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Smoke related deaths from the 2025 season are yet to be determined. However, those whose health could be affected by poor air quality is expected to be more than 20 million.

Smoke inhalation isn’t the only damaging effect caused by wildfires, wildfires can also damage local vegetation. The specific effects will vary depending on the ecosystem and intensity of the fire. Vegetation is the catalyst for how fast a fire spreads and the reason they can be so hard to contain, more vegetation means a larger; faster spreading fire. Ironically, there is one big benefit to having a wildfire. Wildfires can release nutrients into the soil which can help promote regrowth of the area.

Ash from burnt vegetation is full of nutrients, which can act as fertilizer for a new wave of plants. However, invasive plants also have an opportunity to repopulate the affected areas, especially in areas where vegetation is not adapted to surviving wildfires.

This rapidly changing vegetation after a wildfire can have rippling effects, especially for the local animal population. Invasive plants can repopulate and outcompete local vegetation. The new vegetation may not be capable of supporting the animal life in the area. The new vegetation could be poisons or may be unable to provide shelter to the animals living in the region.

The immediate effects on the animal population occur during the fire. Animals need to escape the smoke and flames in order to survive. Evacuation routes and trails could be blocked by fire, leaving ground based animals with no way to out. Others could be too slow to escape and could be overcome by fire and smoke. Those that survive the fire face new challenges. Birds may no longer have trees that can support their nests, herbivores could have less food available due to the loss of vegetation and carnivores and predatory animals could have less meat available due to the decrease in pray.

Where Wildfires Occur and Why Was California so Dangerous

Wildfires occur all over the world. According to the European Space Agency, wildfires burn approximately 1.5 million square miles of our planet each year, about half the size of the United States. Any forested area has the potential to be affected in some way by a wildfire. However, are some wooded areas more at risk for a wildfire than others?

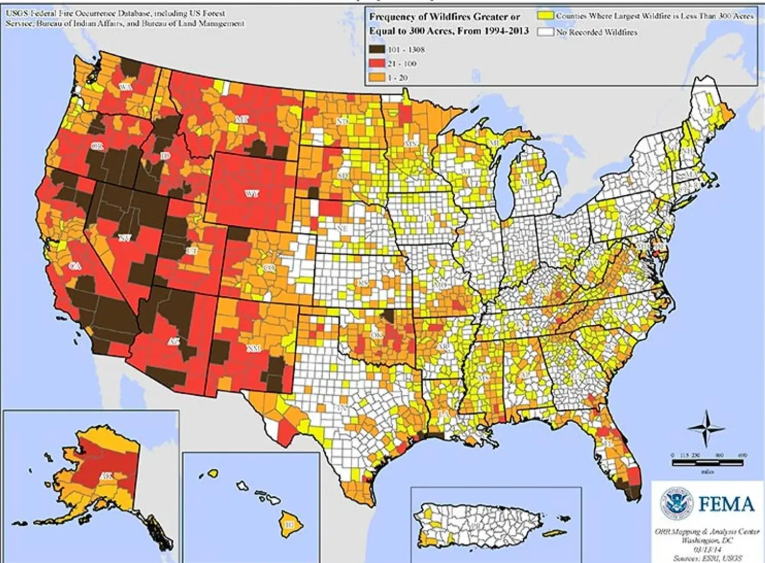

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) attempted to answer this question. When mapping the locations of wildfires larger than 300 acres in size between 1994 and 2013, a pattern emerged. The two highest frequency categories: 101-1308 fires (brown) and 21-100 fires (red) nearly exclusively affect the western U.S.

So what makes the western United States so prone to large wildfires? For one, the region is much drier than other parts of the country. However, the type of vegetation is also a contributing factor. Western and southern states contain a higher amount of dry shrubs, grasses and pines. These plants have evolved to survive the dry summers and are much more flammable. Other trees such as Birch, Beech and Maple trees require moistier soil and a longer rainy season to survive. The high water content needed by these plants makes them less flammable and less likely to sustain a large scale wildfire.

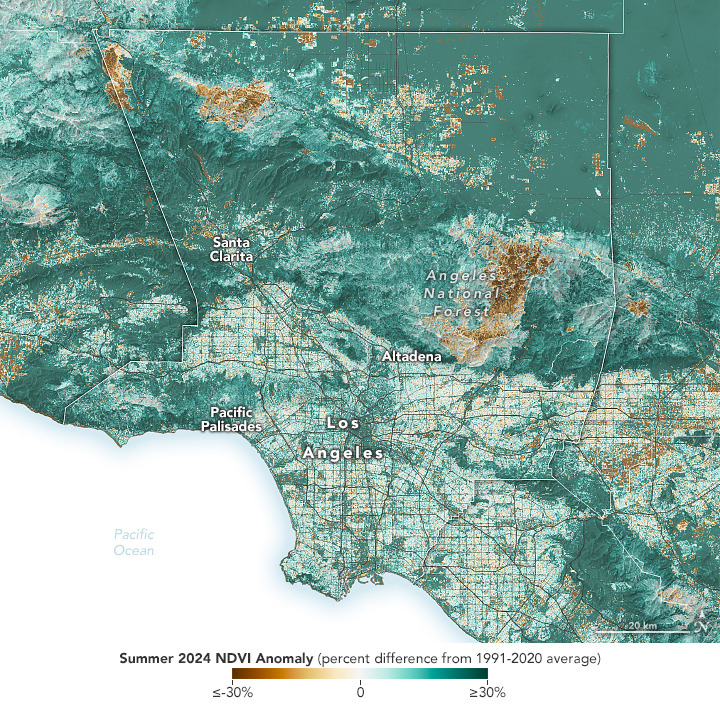

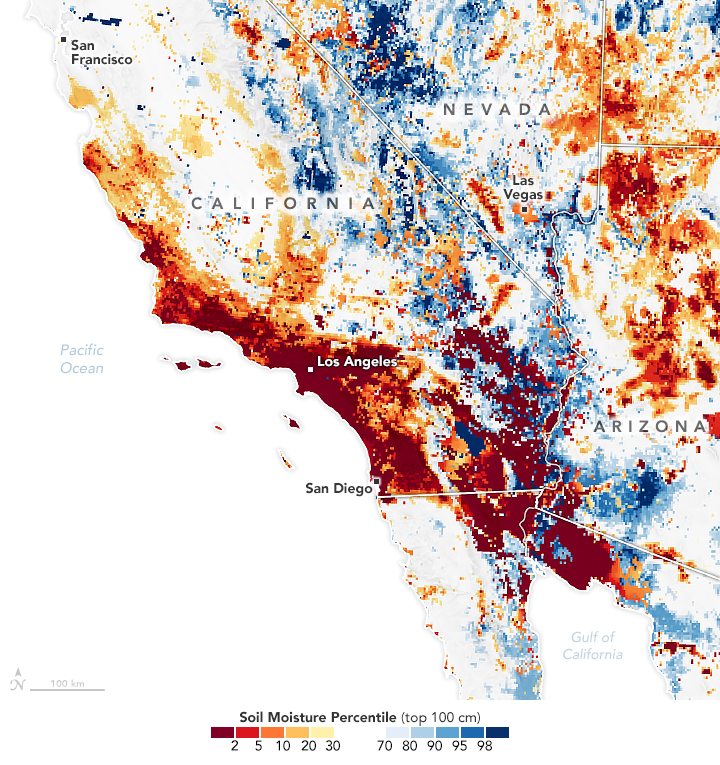

In Southern California, the seeds for the 2025 California wildfires were planted back in 2022. Researchers at UCLA noted that between 2022 and 2024 Southern California received nearly twice the long term average of rainfall. The increased rainfall prompted the growth of local vegetation, with some areas of Los Angeles seeing a 30% increase in green plants.

While the start of 2024 was wet for Southern California, the second half became very dry, receiving no significant rainfall between May 2024 and January 2025, making it the second driest on record. Heat waves in June and July 2024 dried out whatever vegetation remains and on January 7th, the perfect firestorm erupted. An increase of dried vegetation meant there was an abundance of fuel, all that was needed was a spark.

How Wildfires Actually Start

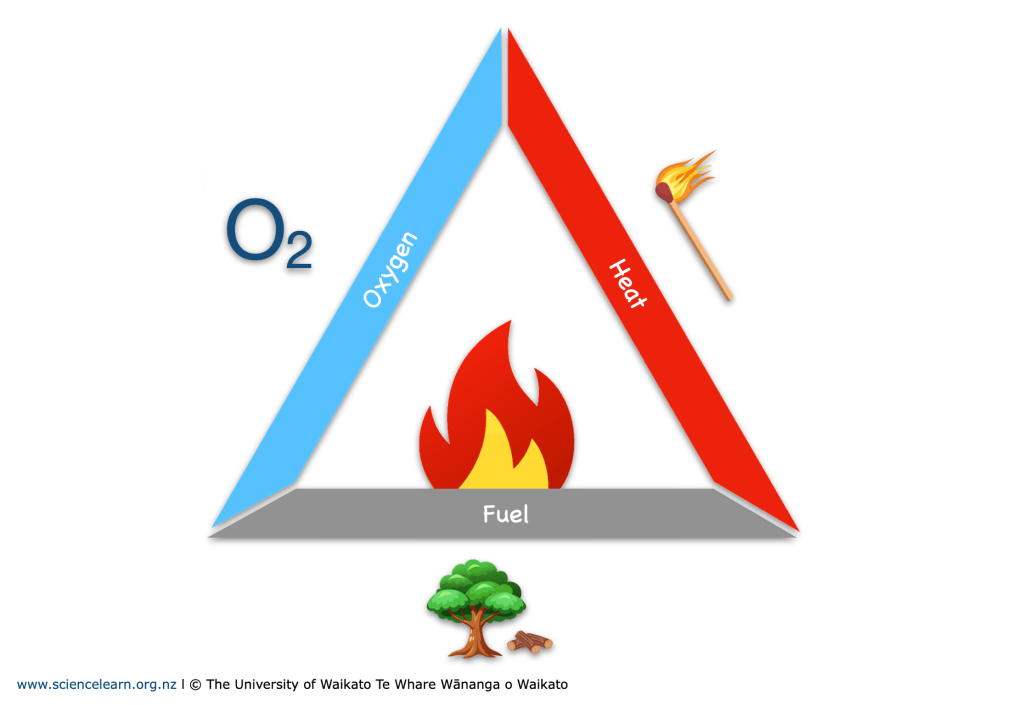

Wildfires behave like any other fire. To start a fire, three things have to be present; Oxygen, Heat and Fuel. This is known as the fire triangle. Oxygen is present in the air we breath and fuel comes from dried out vegetation. Even with two sides of the triangle present, a fire cannot start without a heat source.

The abundance of vegetation and oxygen means two sides of the fire triangle are present almost every day of every summer. However, what about the third side, where does the source of heat come from? Even on Earth’s hottest days the temperature isn’t anywhere close to starting a fire. Some ignition sources could be from lightening strikes or lava flows during a volcano eruption, but these are extremely rare. Sadly, in most cases, the source of the heat is from humans.

It is hard to estimate the exact percentage of wildfires that have been started by humans, most studies estimate that between 85% and 90% of wildfires are started by humans. Everything from an unattended campfire, vehicle malfunctions, arson and carelessly disposed cigarette butts all have the potential to spark an uncontrolled wildfire.

Cigarette butts are the most littered item in the world according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and makes up between 25% to 40% of all global litter collected. John Hopkins estimates that 1.25 billion people globally used tobacco products and 4.5 trillion cigarette butts are littered every year. All it takes is one cigarette to start the next wildfire.

Campfires are another common source of wildfires. Ambers from the fire can travel via the wind and ignite in a new area. Smithsonian Magazine reported that 5% of all wildfires were started by campfires, fireworks or children playing with matches. Other studies report the number is over 40%. Regardless, this is why it is so important to be responsible when spending time outdoors or playing with any type of heat source. Make sure your campfires are fully extinguished. Don’ just wet the area within the campfire, be sure to wet the surrounding area as well. It’s also a good idea to stick around and observe the area for about 30 minutes after, just in case any stray ambers relight.

Fighting and Containing Wildfires

Fighting a structure fire is very different than fighting a forest fire. We might assume a fire fighter can handle any type of fire, however that isn’t the case. Fire fighter who handle wildfires (called foresters in some articles) often receive specialized training. The first major difference is a wildfire isn’t contained to a structure. Wildfires can be hundreds of acres in size and spread across all different types of terrain. Unless the fire is small in size, spraying water isn’t as effective and more indirect methods are needed. Since removing heat from a fire hundreds of acres in size is quite difficult and oxygen is all around us, these indirect methods often involve removing the vegetation (fuel).

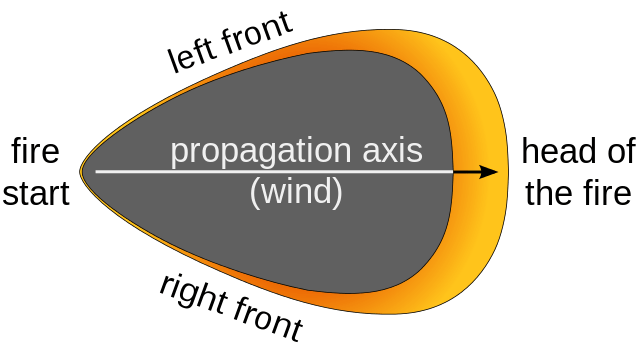

Foresters first start by establishing a front line. Where the fire is heading (called the head) and the left and right fronts. Once these front are established, foresters will use dozers to set up a containment line around the perimeter, in the direction of travel, around the fire.

These dozers (or excavators) remove all vegetation, so the fire cannot spread. By removing all the vegetation down to the bare soil/rock, there is no more fuel to support a burn. Once a containment line is established, foresters can begin to use other methods to create a fire line to stop the flames.

One method for controlling the flames is through water drops. These drops need to be strategic in their location. If the fire is too hot, the water could evaporate before effectively cooling the fire. Instead foresters can add gels and surfactants to the water to make it more effective at soaking the area and cool the flames. Other times water can be dropped ahead of the fire to dampen the area and slow the spread.

Fire retardants are also frequently dropped from the air as a means to control wildfires. The exact mixture can vary depending on the size of the fire, the material that is burning and surrounding area (plants vs budlings). These are generally dropped around the perimeter to help slow the fires progress.

Under normal conditions the cellulose in the plant decomposes as it’s heated, producing Oxygen which fuels the fire. The retardant interacts with the cellulose and consumes heat from the approaching fire. The result is a non-flammable product that does not support a flame.

Another method for controlling a wildfire is through controlled burns. Controlled burns are exactly what they sound like, foresters will burn a section of forest that’s ahead of the flames. The burning will use up the fuel, so when the flames reach this line, there’s nothing that can support a flame and the fire goes out.

Fighting fire with fire is a literally what foresters do when performing these controlled burns. Controlled burns often occur within the containment lines ahead of the fire and will starve the fire of fuel. However, they need to be performed with extreme caution and care.

Containing a wildfire by any of the methods listed is very challenging. Having a containment line doesn’t guarantee that a wildfire will stop spreading. Wildfires can spread through the roots underground or by ambers carried by the wind. Hotspots can reignite outside the perimeter and the fire can spread. Scouts must be present along the control line during the fire fighting operation to check for hot spots that could reignite. Fighting wildfires is a huge undertaking and requires a lot of resources. Agencies must be committed to supporting crews that can deploy at a moments notice. If agencies cannot provide support and the crews do not have the resources required, wildfires will get worse.

Prevention

Controlled burns have recently come under scrutiny by government agencies. In October 2024 the U.S Forest Service announced that it would stop controlled burns (called prescribed burns in some articles) for the foreseeable future in California. The decision came as a way to preserve the availability of staff and equipment in case of potential wildfires. While the state is responsible for maintaining state owned parks, the federal government is responsible for areas outside state and local control. Long term funding for wildfire control and prevention is often unreliable and frequently tied up in congressional budget debates.

An example of congressional funding affecting wildfires was in August 2021 in the El Dorado National Forest near the town of Grizzly Flats. Back in 2013 the Forest Service identified this area as being high risk for a potential fire and presented a plan (The Trestle Project) to mitigate the risk. The project was supposed to be completed in 2020. However, by the finish date only 14% (2,137 acres of the planned 15,000) of the land had been remediated. The project faced numerous staffing shortages, inconsistent budgets, and pushback from local environmental groups. In August 2021 a fire erupted and 48 hours later, Grizzly Flats was leveled.

This is what can happen if government and environmental activist groups get in the way of preserving the wilderness. The desire to preserve the land by “leave it as it is” mindset actually destroyed the once beautiful landscape. Vegetation control could be the key to saving these areas.

Recently an organization called Save The Redwoods has advocated that “cultural burns” (same idea as controlled or prescribed burns) could help save the Redwood and Sequoia Forests. A cultural burn is the practice of burning dried vegetation for spiritual beliefs or cultural rituals. Outlawed by California in 1850, these burns were often performed by local tribes or indigenous people. California lifted the ban in 2022, but not before more than 20% of the giant mature sequoia trees died in extreme wildfires in 2020 and 2021. The fuel for these fires was thought to be the buildup of dried out vegetation. Shine Nieto, vice chairman of the Tule River Indian Tribe says “The cultural burn works because our people have been doing it for centuries and centuries,” (Credit: Kristina Malsberger of savetheredwood.org).

Conclusion

The idea of deliberately lighting part of the forest on fire to prevent wildfires may seem counterproductive. However, when considering the potential damage dried and overgrown vegetation can cause, it is a small price to pay in order to preserve our wilderness.

Of course, the best way to prevent a wildfire is to be responsible. Make sure your campfires are fully extinguished by dumping water on them and the surrounding areas. Do not carelessly dispose of your cigarette butts out the window of your car, or in the bush next to the sidewalk.

We may never know what foresters go through when fighting a wildfire, but we can make sure we do our part to ensure their safety on the front lines. In a world where the climate is changing, rainy and dry season are becoming more extreme; these small steps can ensure that we are minimizing the risk of the next wildfire.

References

- https://www.aa.com.tr/en/americas/southern-california-wildfires-fully-contained-after-24-days/3468561

- https://ctif.org/news/how-did-smouldering-root-fire-new-years-eve-turn-deadly-2025-la-fires

- https://www.epa.gov/california-wildfires

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/154641/widespread-smoke-from-canadian-fires

- https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2025/02/how-do-wildfires-impact-the-environment/

- https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2025/02/how-do-wildfires-impact-plants/

- https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2023/09/how-wildfires-impact-wildlife/

- https://weather.com/news/news/where-large-fires-are-most-common

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/153896/fuel-for-california-fires

- https://wfca.com/wildfire-articles/where-do-wildfires-occur/

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/wildfire-causes-and-evaluation.htm

- https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2021/12/explainer-how-wildfires-start-and-spread/

- https://hub.jhu.edu/2024/04/22/cigarette-butt-filter-litter/

- https://wvforestry.com/how-foresters-fight-wildfires/

- https://wfca.com/wildfire-articles/prevent-the-spread-of-wildfires/

- https://www.npr.org/2025/01/10/nx-s1-5254179/los-angeles-wildfires-flame-retardant

- https://cepr.net/publications/us-forest-service-decision-to-halt-prescribed-burns-in-california-is-history-repeating/

- https://www.savetheredwoods.org/redwoods-magazine/autumn-winter-2024/banned-for-100-years-cultural-burns-could-save-sequoias/

- https://www.capradio.org/articles/2022/08/16/stalled-us-forest-service-project-could-have-protected-california-town-from-caldor-fire-destruction/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/study-shows-84-wildfires-caused-humans-180962315/