We often hear about plastics being one of the most detrimental things to the environment and that we should ban them outright. However, managing plastics may not be that simple. Plastic is in everything: from straws and utensils; to toys, vehicles, electronics; and all throughout our homes. An overnight nationwide ban would cause massive problems to nearly every industry. Any legislative action against plastics needs to be carefully drafted to not disrupt any essential items, like plastic medical devices.

Why We Use Plastic

The first synthetic plastic was invented in 1869 by John Wesley Hyatt. A sudden increase in billboards had put a massive strain on natural ivory (which came from slaughtering elephants). Hyatt began treating cotton fiber cellulose with camphor, and he discovered that the resulting material can be shaped and molded to imitate nearly all natural substances. This was groundbreaking for the working industry because it was the first time production was not limited by the availability of natural resources.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the working industry knew natural resources were limited and alternatives needed to be developed. In 1907, Leo Baekeland invented Bakelite. This was marketed as the first fully synthetic plastic, meaning it contained no natural molecules or substances. This new material initially served as an insulator due to its heat resistant prosperities. As manufacturers continued to research this product, its tensile strength, durability and flexibility were better than anything before it, meaning the uses became endless.

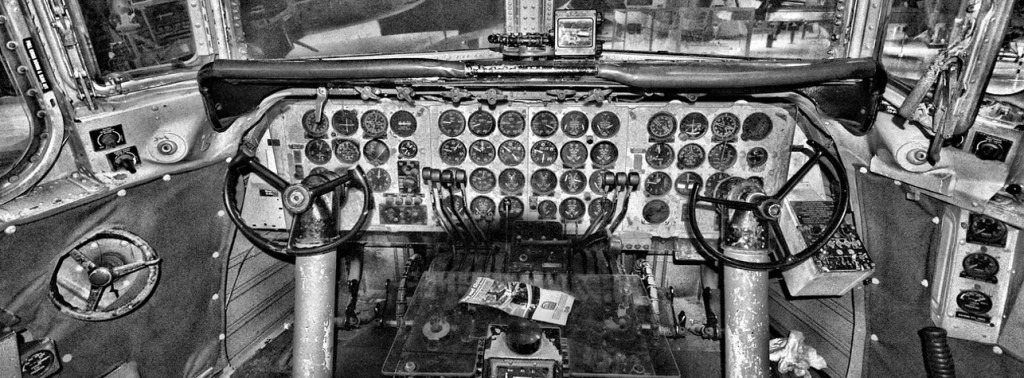

As the depression, WWI and WWII strained global resources, the need for cheap, artificial synthetics not constrained by natural resources became vital. Nylon was developed as a synthetic silk and was used in parachutes. Plexiglass was developed to replace glass in airplane windows. As the war progressed, plastics became even more vital due to their malleability and cost effectiveness. They were used in everything from insulation (polyvinylchloride) to flight deck displays, goggles, and weapons including some parts of the atomic bomb.

After the war, plastic production continued to expand, and by the 1950’s-1970’s, plastic was taking over the world. Plastics replaced steel in cars and wood in furniture, while also being used in home insulation, electrical cables, tires, jewelry, electronics, flooring, and so much more.

Benefits of Plastic Items

Plastic wouldn’t have become so widespread if there were no benefits. In addition to being cheap to produce, lightweight and durable, plastic also helped improve human health.

Food and water is essential for human survival. Plastic water bottles and food packaging made the long term storage and transport of food and water possible. Vital resources could now be mass delivered to areas that once had a very limited supply. Areas affected by natural disasters were able to get lifesaving food and water delivered within hours thanks to mass produced plastic.

Plastic also helped improve irrigation systems. Areas that were once unable to support any crops, flourished with life. This allowed humans to survive in areas that were once unlivable. These same designs helped mitigate storm water runoff and improve land drainage to prevent localized flooding after heavy rainstorms.

Plastic also had some economic benefits. A study conducted in January 2005 (GUA Gesellschaft, 2005) aimed to investigate the emissions produced by aircrafts during the transportation of plastic, glass and metal items. They discovered across Europe that items packed in plastic reduced energy consumption by 52% and greenhouse gas emissions by 55%, which equates to 4.3 million tonnes of CO2 reduction. It was concluded that the lighter packing material of plastic items results in a lighter vehicle weight. A lighter vehicle weight results in more fuel savings and reduced emissions.

Another study conducted in August 2006 (Gehm, 2006) looked to identify weight differences between vehicles and planes made of metal and plastic. With regards to airplanes, they found that the Boeing 787 has an interior that is 100% plastic composite and an exterior that is 50% plastic composite. This transition to plastic translates to a 20% fuel savings. With regards to vehicles, replacing metal parts with plastic reduced the overall weight by 12%. The reduction in weight translates to a 20-30% in fuel savings.

Another study also conducted in 2006 (Hocking 2006) aimed to measure the energy expenditure between manufacturing a disposable polystyrene cup compared to a reusable ceramic cup. When factoring in repeated cleaning, they discovered that it would take several hundred years for a reusable ceramic cup to match the energy produced from manufacturing a polystyrene cup. A separate study conducted by the Dutch Research Institute in 2007 confirmed the findings.

Composition and Manufacturing

One of the benefits of plastic is there was very little dependency on natural resources. However, the manufacturing process isn’t fully free from requiring resources.

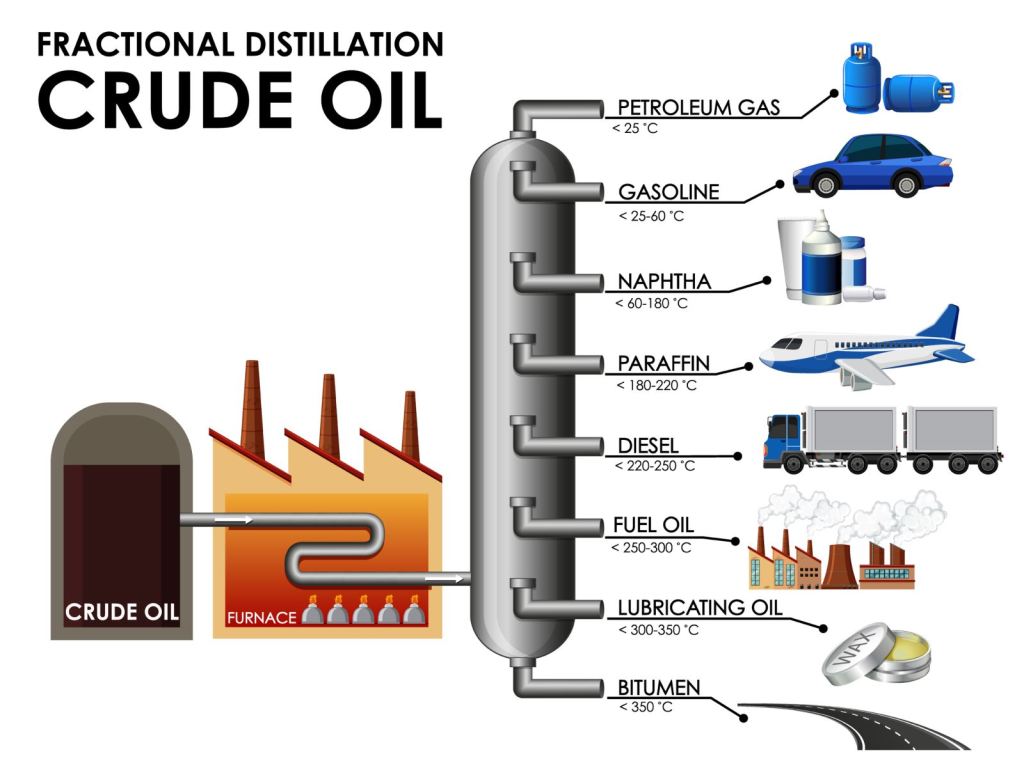

The initial step in producing plastic is to extract raw materials from the Earth. Crude oil is most common material. This is essential because Crude Oil contains a large amount of carbon necessary for production. These carbon chains are called hydrocarbons and are the building blocks for most products in everyday life.

The next step is to refine the oil into different petroleum products (pictured above). This step involves heating the crude oil in a furnace. Once heated the material is sent to a distillation unit where the various products, called fractions, are separated by weight. The fraction used in the production of plastic is called Naphtha. Naphtha specifically has a 5 to 10 carbons molecule chains.

The next step involves joining several of these Naphtha molecules into a longer chain to produce polyethylene. The process of joining these chains together varies depending on the specific plastic being created. Polyethylene is processed in a factory to create plastic pellets. These pellets can either be sold or reheated and recast in another mold.

Since the production of plastic is heavily dependent on the extraction of crude oil and refining carbon. So, while the process doesn’t consume natural resources such as vegetation or wildlife, it does involve the use of oil for production. Then the question becomes, is it possible to create plastic without crude oil extraction? The answer is yes, these plastics are marketed as bioplastics or biobased plastics. Instead of oil, the active ingredients can range from carbohydrates, vegetable oils and fats, bacteria, and cellulose among others. Bioplastics are not automatically more sustainable than regular plastics. The main difference is the way they break down after use. Bio plastics will be discussed later.

Recycling and Effects on Health and the Environment

Until now, the benefits of plastic are clear. However, there are some drawbacks to producing a near fully artificial substance on such a large scale. Marine life is at the highest risk for ingesting, suffocating or becoming entangled in plastic debris due to plastic products leaching into oceans and transported by currents.

As plastic gets disposed of, it ends up in waste facilities and landfills. Not all plastic can be recycled; there are many factors that affect how easily plastic is recycled. The plastic Resin Identification Codes (RICs or RIN) were created in 1988 by legislators in response to the public believing plastic to be harmful. RICs are the various numbers 1-7 printed on different types of plastic containers. The specific number indicates the composition of the material.

From the beginning, the average person would not understand the purpose of the number and symbol. They would see the symbol and believe it to be recyclable even though it wasn’t. Recycling agencies also believed that widespread recycling of plastic was not economical. These RICs helped reinforce to the public that widespread recycling was possible and effective.

While 30% of numbers 1 and 2 are recyclable, numbers 3-5 are much harder to recycle, and 6 and 7 are nearly impossible to recycle. Since the RIC was never trademarked, the symbols were used by lobbyists and activist groups to trick the public to believing that recycling was working. In reality, most plastic, even if placed in a recycling bin, ends up in landfills. For example, the small size of plastic caps can easily be missed by shredders, and the flimsiness of plastic bags can easily choke and shut down recyclers. The process of handling and processing the material after use causes it to break down into small bead-like materials called microplastics, which ultimately ends up in our parks, rivers, oceans.

Microplastics are the main source of pollution from plastic products. They are compromised of small plastic particles, 5 millimeters or less in size, and broken down from larger plastic products. These microplastics are the source of pollution and pose the greatest risk to the environment.

The first risk is ingesting plastic that is not made for consumption. EPA research suggests that more than 1,500 species of marine life have ingested some type of plastic. These plastic products can accumulate in animals and be passed on to other species.

Human health effects of plastic ingestion are similar to those of wildlife. Microplastics have been found in human livers, kidneys and placentas. Additionally, cacogenic compounds from plastics can leach into tap water, increasing the risks of endocrine, neurological, cardiovascular and immune disorders. Health effects aren’t the only risk caused by plastics. In 2019 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development attempted to study the greenhouse gas emissions generated by plastic products. Their research suggests that plastics contribute to 3.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with 90% coming from their production.

Plastics that remain intact can result in wildlife becoming entangled. The image to the right shows a turtle who became entangled in plastic used to store soda cans. Material like this is hard to manage by a recycling shredder. An item like this can easily be carried from a landfill or recycling facility into nature by wind or rain.

Plastic that ends up in the ocean can be pushed thousands of miles into the Pacific or Atlantic oceans. In fact, one of these patches has a name, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This patch consists of two smaller patches, the western patch off the coast of Japan and the eastern patch between Hawaii and California. The Subtropical Convergence Zone is located a few hundred Kilometers (~200 miles) north of Hawaii. This is where the warm south pacific water meets the cooler water of the artic. Much like air, warm water at the equator will travel north up the coast of Japan to the artic where it cools and travels south between Hawaii and California back to the equator. Due to Earths rotation, warm water at the equator travels west (towards Japan) while cooler water in the artic travels east (towards Alaska). The center of this current system is very stable, allowing trash and other pollutants to accumulate at its center. This rotating vortex of ocean currents serves as a large highway to move pollutants across a large ecosystem, affecting many forms of marine life.

The Push Toward Paper

Paper is one of the oldest forms of “flexible packing,” in which sheets of treated mulberry bark were used by the Chinese to wrap foods as early as the first century B.C. Of course the process has changed a lot since the first century, but the uses haven’t changed much. Commercial boxes were produced in 1817, paper bags in 1844 and cartons in the 1870s. Paper was used to transport cereal and other dry foods, consumer goods like clothing and electronics, and sealed paper was used to transport liquids like milk.

By the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the use of paper began to fade as plastic took over the manufacturing and packaging scene. However, in the late 1980s and 1990s, paper began to make a comeback amidst growing environmental concerns over plastic. By the early 2000s, there was worldwide action against plastic. In 2002, Bangladesh became the first country to ban thinner use plastics. In 2007, San Francisco was the first city in the United States to ban single use plastics in super markets.

By the 2010s, there was a large push toward reusable bags. California became the first U.S state to implement a statewide ban on plastic bags in 2014. Then, New York joined the list of U.S states banning single use plastic bags in 2019 in an effort to promote reusable paper technology. Some businesses took reusable technology to the next level by offering discounts to those who bring reusable bags. Others offered reusable bags for promotions and marketing.

The Manufacturing Process

If paper was the perfect solution to our commerce problem, then why haven’t businesses and manufactures been producing paper on a large scale? The process of making paper that is viable for general use is quite invasive.

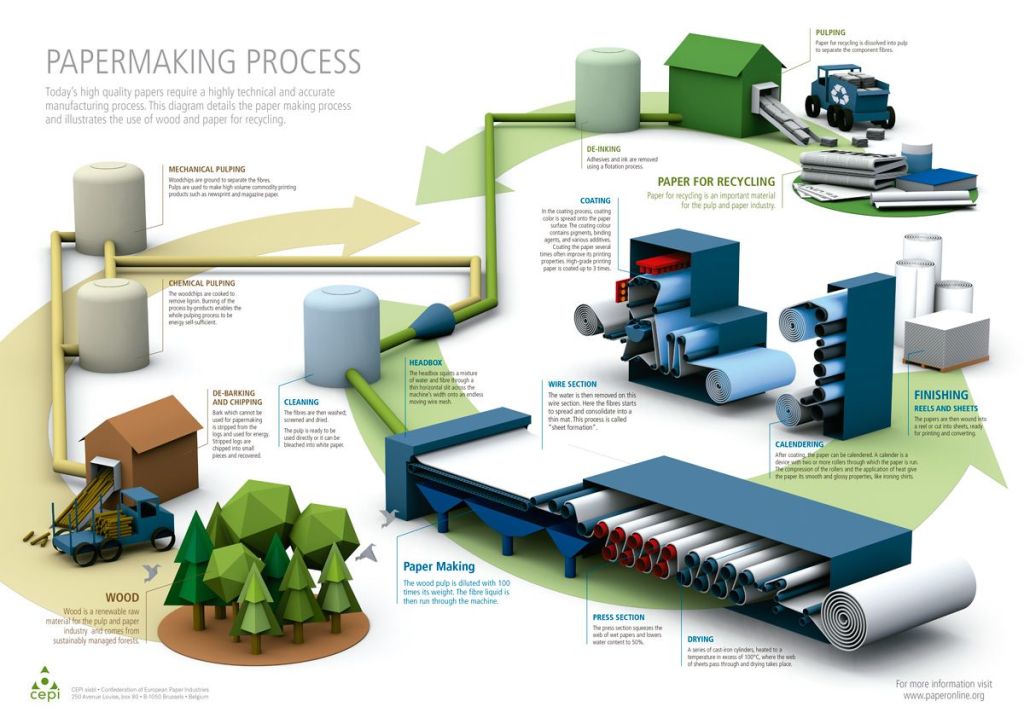

The first step in paper production is to harvest virgin wood from forests. The next step is to remove the bark and chip the wood. It is estimated that 17 trees are needed to produce one tonne of white paper. Once there is enough, the chips are heated to extract lignin, a structural polymer found in the cell walls of tree bark. The paste is mixed with a lot of water to spread the fibers. The sheet is then pressed to remove excess water and reduce the weight. Lastly, the paper is dried and re-pressed to produce the shiny finished product.

Paper that is recycled is first di-inked using chemical additives and will join the production process at the stage where water is added to the paste material (pulp making). Regardless of whether paper is manufactured or recycled, the process uses a lot of water and produces a lot of water waste. As much as 10 liters of water (~2.5 gallons) are needed to produce one sheet of paper. Water is essential for all life, and during droughts, may not be readily available.

The Drawbacks of Paper

The manufacturing process has some pretty serious drawbacks. The most obvious drawback is it consumes valuable resources. Almost all paper is made from cellulose, which is a vital structural component of plants. This means in order to produce paper, we need to consume valuable natural resources, which can be limiting. This consumption of natural resources was one of the reasons synthetic plastic was created in the early 1900s, to preserve natural resources.

The second major negative to the use of paper is it contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions during its production. It is estimated that paper productions account for 9% of all energy consumption and 2.5% of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.

CO2 and methane are the most common gases emitted. Nitrogen Oxide (NO2) and Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) are also released during the production process. These gasses are directly linked to heart and lung problems, cancers and other cardiovascular problems.

The water produced by the pulping process is also saturated with chlorine dioxide, which is harmful to human health and toxic to marine life. Effluent water can reach natural bodies and affect drinking water and marine life. Sludges containing halogens, phenols and inorganic salts (like sodium and potassium chloride) are also a byproduct of producing paper during the pulping process.

The di-inking process also produces its own waste, often containing volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Examples of VOCs include methanol, formaldehyde, ethylene glycol and others. During the de-inking process, these chemicals can be off-gassed through emissions, or captured in water and processed as hazardous waste. Recycling the sludges, de-inking wastes and wastewaters is not always possible due to their high halogen or organic content.

Which is Better?

So which one is better for the environment? Overall both paper and plastic produce greenhouse gases during their production. Plastic production contributes about 3.4% of greenhouse gas emissions, while paper contributes about 2.5%. Plastic uses very few natural resources but doesn’t break down easily, while paper consumes a large amount of resources but breaks down faster (~5 years).

You might think a substance that breaks down in the environment faster and doesn’t persist in nature would overall be better. However, when considering that plastic is linked to reduced CO2 vehicle emissions and contributes to providing clean and safe food and water to resource stricken communities; the answer isn’t as clear anymore.

Careful readers will also note two facts that appear to contradict each other. The first is the European study indicating that plastics reduce CO2 emissions by over 50% compared to other materials. However, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development notes that plastics contribute to greenhouse gasses. These two studies show a telling story regarding plastics as a whole. While their production creates CO2 and greenhouse gasses, they make up for it with their reduced transportation costs and fuel savings.

So what is the answer? Is paper really better? The answer depends on the use and process. Plastic is best for storing and transporting pharmaceuticals, food, and water due to its ability to provide an airtight seal and keep out moisture. Plastic is also best for products that we don’t want to break down, such as irrigation or plumbing pipes, parts for vehicles, and items that have to be durable.

However, paper is best for items that do not require climate or temperature controls or items that just require a medium for transport (like a box). Things like oats, rice and other dry consumables can all be packaged in paper or cardboard. Shipping articles of clothing, some electronics, and personal products use paper packing as the preferred mode of transport. Paper is also great for reusable items like bags and boxes. Some manufacturers will wrap the specific item in a small amount of plastic (bubble wrap) and ship surrounded by paper packing and in a cardboard box. This reduces the amount of plastic used to only what is essential for a safe transport.

Alternatives?

Both paper and plastic have their negative effects on the environment. Is there a material that doesn’t consume resources, produces very little CO2 and doesn’t persist in the environment? One alternative is bioplastics, which are made from non-renewable sources such as vegetable oil, carbohydrates, recycled food waste and bacteria instead of crude oil and naphtha. The first bioplastics were made from bacteria in 1926 by Maurice Lemoigne. As microbes consume sugar, they produce polymers that can be used in production. Henry Ford also used plastic made from soy in the 1940s.

The main difference between traditional plastic and bioplastics is how they break down. Bioplastics can degrade quicker, just a few months to years. However, they may not break down in all climates. They are most commonly made for single-use plastics, like water bottles and packing films.

Telling the difference between regular plastic and bioplastics can be challenging. All bioplastics must have the letters PLA under an RIC (3 arrows forming a triangle) with the number 7 inside. Research surrounding bioplastics is still ongoing, and while it will not solve the plastic pollution problem, it can provide an alternative.

Researchers are also looking for ways to break down existing plastic. In 2016, researchers at a recycling center in Japan discovered a plastic eating bacteria on a water bottle. Ideonella sakaiensis survives by consuming Polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The bacteria converts the PET in the plastic into ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. This discovery has prompted further research into engineering bacteria to breakdown the plastic that already exists in landfills and oceans. Since bacteria are found in all corners of the world and in all environments, it is not surprising that researchers have found one species that can survive by eating plastic.

At the moment there is no compound that is 100% eco-friendly that provides the versatility of plastic. Glass and metal are very heavy, expensive and are not as versatile as plastic. Plastic as a compound isn’t going anywhere, not until a replacement is found. Since all the plastic ever made is still polluting Earth, the focus of research should be on how to remove what’s already causing harm, and develop a way to remove future plastic contamination.

References

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/classroom-activities/role-playing-games/case-of-plastics/history-and-future-of-plastics/

- https://advancedplastiform.com/the-history-of-plastics-part-ii-1935-through-1980/

- https://www.solentplastics.co.uk/news/how-plastic-was-crucial-to-the-war-effort/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2873019/

- GUA Gesellschaft für umfassende Analysen GmbH 2005. The Contribution of Plastic Products to Resource Efficiency Sechshauser Straße 83, A-1150 Vienna; pp 57–58

- Gehm R.2006. Plastic on the outside. Automotive Engineering International. August

- Hocking M. B.2006. Reusable and disposable cups: an energy-based evaluation. Environ. Manag. 18, 889–899

- https://www.bpf.co.uk/plastipedia/how-is-plastic-made.aspx

- https://www.epa.gov/plastics/impacts-plastic-pollution

- https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/stories/true-cost-plastic-pollution

- https://www.earthday.org/plastic-recycling-is-a-lie/

- https://trellis.net/article/history-plastic-resin-identification-codes-recycling/

- https://www.clf.org/blog/cant-recycle-out-of-plastic-pollution-problem-guide/

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

- https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/cdfs-133

- https://earthwarriorlifestyle.com/blogs/news/the-evolution-of-bags-a-historical-journey-from-paper-to-plastic-to-reusable

- https://www.smithcorona.com/blog/market-shift-from-plastic-to-paper/

- https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/resources/paper-based-products-as-promising-substitutes-for-plastics-in-the-context-of-bans-on-non-biodegradables/

- https://kunakair.com/environmental-impact-paper-industry/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06962-0

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666278724000369

- https://www.deskera.com/blog/the-pros-and-cons-of-paper-manufacturing/

- https://www.swiftpak.co.uk/insights/plastic-vs-paper-packaging-the-pros-and-cons

- https://www.compostnashville.org/blog/bioplastics-vs-traditional-plastics

- https://big.ucdavis.edu/blog/plastic-eating-microbe